Mourning My Father by Open Sourcing Our Code

Tl;dr: I miss my dad. I published some of the code we wrote together.

Background

The phone call was short. I asked how he was feeling, and if they had figured out what was going on yet. Dad evaded. They were still getting answers, he said. That was all I needed to hear. I walked to the nearby park in the Fall air, sat on a bench under a remote tree, and lost my composure.

Sobbing is a really weird sound, I thought to myself. Gasps and sniffs, heaves, tears, borderline hyperventilation. I was not used to hearing these noises come from me, especially when I had nothing more than my gut to inform my fears.

But I'd heard it in his voice. Everything was not alright. The world was ending.

As I grew up, it always seemed a little irrational to me that my deepest terror was losing my dad. At 15 years old, then 20, 25, I never really heard anyone around me talking about how vitally important their dads were to them. And besides, it’s natural that a son lose his father, rather than a father lose his son. Right? And yet, even after the birth of my own sons reoriented my hopes and fears, the only anxiety late at night that could consistently latch onto my mind — and not let go — was how much I couldn’t bear to lose Dad. Now my literal nightmares materialized.

Today is the first aniversary of Pete Garvin's death. He died of cancer 4 weeks after his initial diagnosis. The weather report says it will rain all day today from the hurricane. A family friend told me the rain is from him for us, and I believe her.

My Motivations, In Brief

Before he fell ill, Dad and I would meet one evening a week at his office in Akron and work on little things around his company, Protectus LLC. I had helped him build the technology side of the company for a couple of years when I got out of school, and the weekly get together was a good way to exercise parts of my brain that my full-time jobs did not. It wasn’t lost on me how privileged I was to spend so much time literally being paid to hang out with my own father. When I look at my career so far, I can trace my success to 3 people. Dad is at the top of that list.

I want Dad to be here with me. I want him to look over my shoulder at this stupid website and tell me that he thinks dark mode is harder to read. I want to find a way to keep a part of him alive with me, just a little longer.

So, I’m trying to finalize our last project together.

The Project

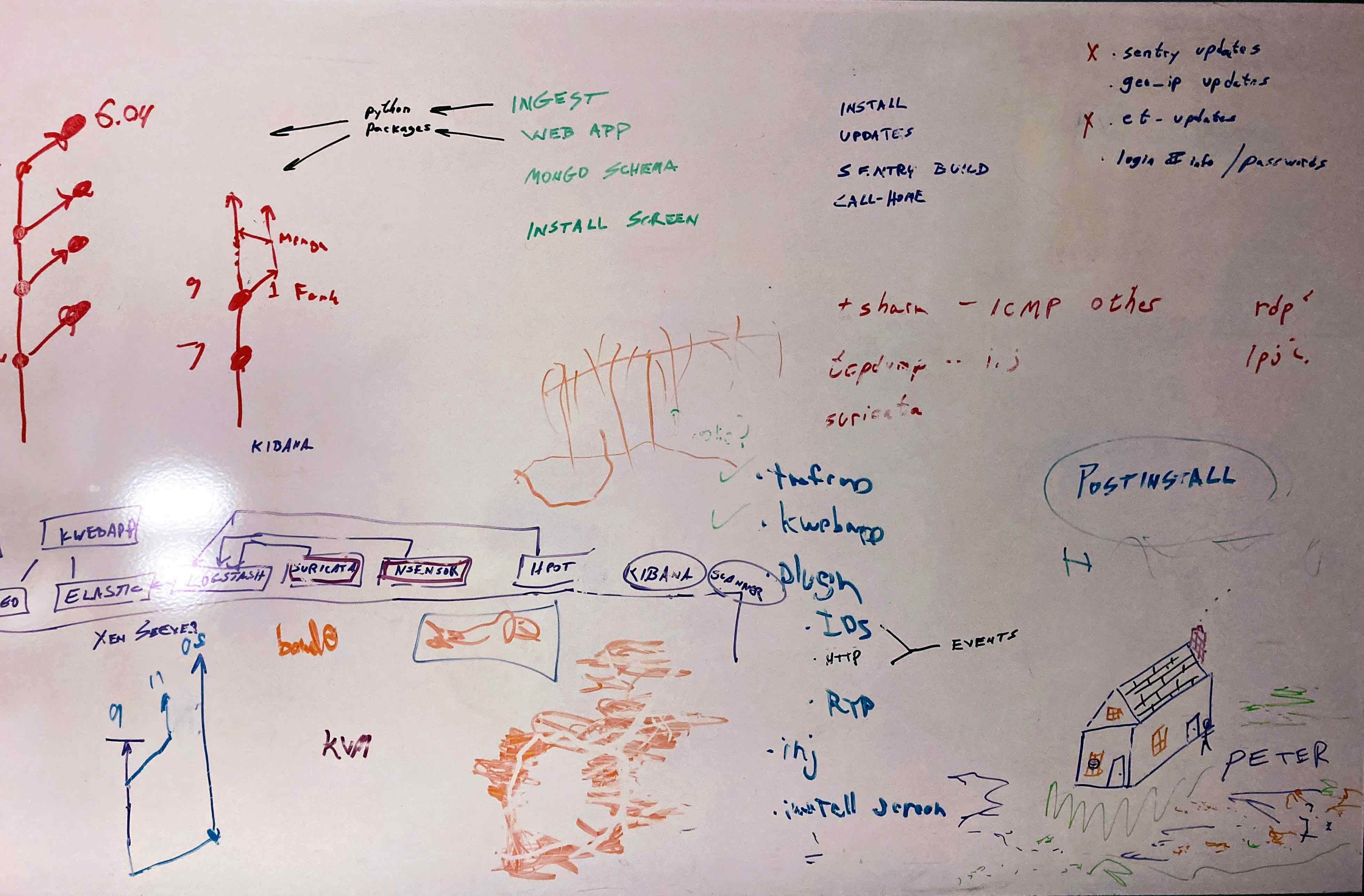

Protectus was built around a product called the Sentry. At its core, the Sentry is a combination network sensor and analytics engine. It reads bytes off the wire, does some deep (and shallow) packet inspection, and dumps information into a local MongoDB database for post-hoc analysis. Then there’s a web app that facilitates queries and reports. I wrote the frontend right out of school, and Dad took responsibility for the ingest script. We designed everything together, spent untold hours in front of the whiteboard diagramming, discussing, and deciding.

This is the last whiteboarding Dad and I did. Notice the contributions for/by my son in the corner. I can't bring myself to erase any of it.

This is the last whiteboarding Dad and I did. Notice the contributions for/by my son in the corner. I can't bring myself to erase any of it.

Neither of us were rockstar developers. Dad’s coding style was informed by C code from the 80s and 90s, with lots of illegible variable names and clever routines that didn't always explain what they were doing. My code architecture was overly clever and immature, abusing inheritance trees and creating all sorts of extranious abstractions that probably have not aged well.

We did do some things right, and shipped new Sentry devices to all our existing customers with a year or two of my coming on board.

The Sentry was not a big commercial success. I left the company for IBM, and Dad eventually decided to shift cleanly from a product + services company to just a services company. The Sentry stopped being the main event for the company, and began to be spoken of as just a tool in the toolbox.

Part of the shift in the Sentry strategy was to open source core parts of the product. We started with the ingest scripts. This involved cleaning up the code a bit, and doing some careful git history surgery. The idea was to publish not just the code, but ship a `pip install`-able module on PyPi.

I’ve given up on shipping an installable Python module. PF_RING dropped their repo for the version of Ubuntu we were using to build on Travis, and I don’t have the time or interest to keep the build running. But I do want to share the code.

The code itself is probably not very interesting unless you're into parsing network traffic or aggregating it into Mongo. There are some instructions for getting a dev build running, if you're really keen. This post isn't really about that.

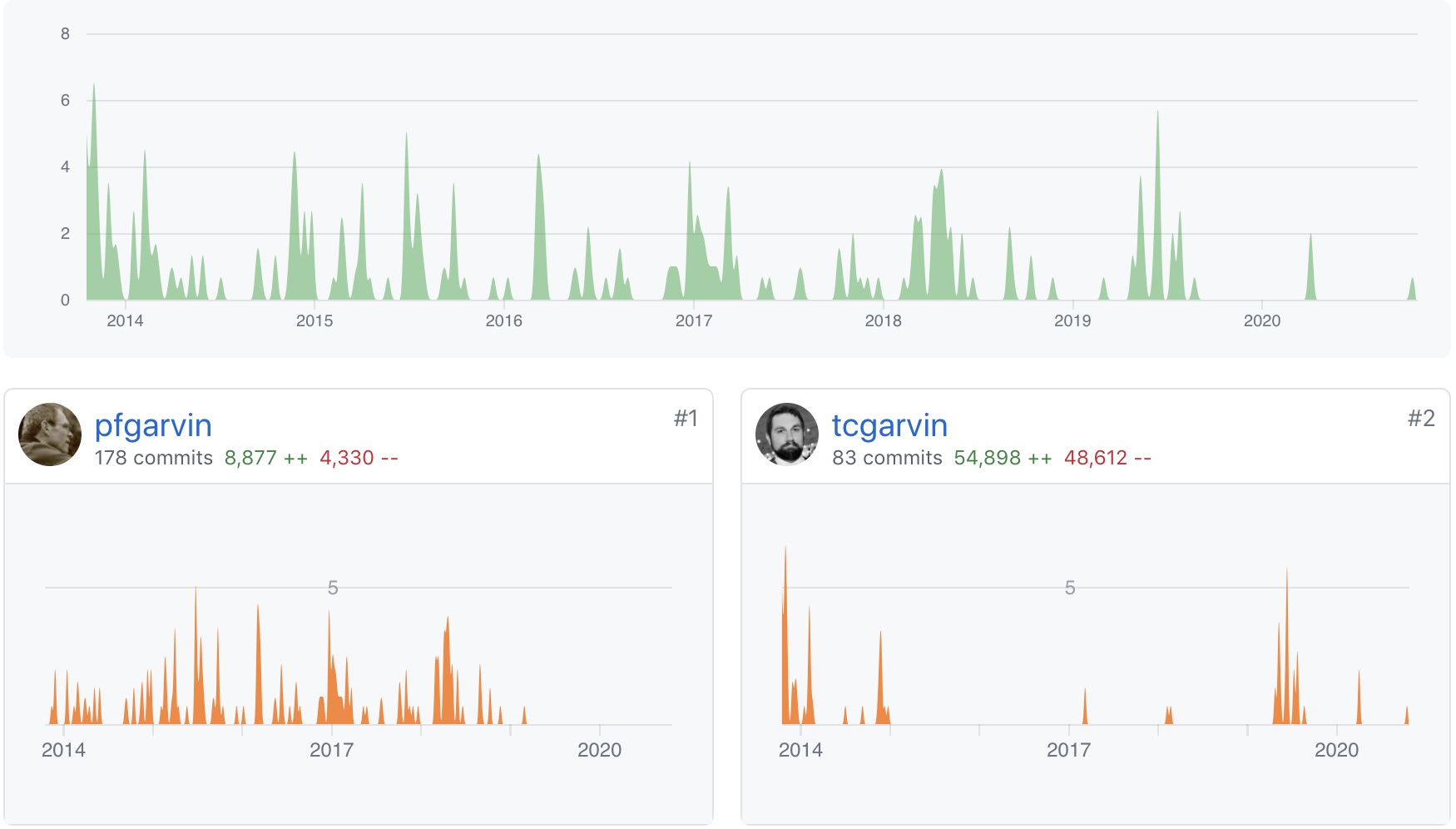

Dad and I wrote all the code. This graph shows a partial history of the ingest code I've released, which was more Dad's than mine.

Dad and I wrote all the code. This graph shows a partial history of the ingest code I've released, which was more Dad's than mine.

Seeing Dad in the Code

In preparing the code to be released, I spent some time browsing git history and its contents. At first I was caught off guard by how potent seeing his comments was. It’s not like he left jokes around or anything, but this this codebase (including a lot that I’m not open sourcing today) has his heart and soul in it.

268# Adding vlan id - PFG - April 2014

269# No way of knowing how long the packet is so add vlan id after timestamp.

270# If field after timestamp contains dots or colons, then it is a src (mac or ip).

271# Otherwise, it must be a vlan id.

272if pkt and not doc:

273 # If no vlan id present

274 if b'.' in pkt[1] or b':' in pkt[1]:

275 if pkt[4] in pc.leaked_protos_to_ignore: return (), []

276 msg = pkt[5]

277 for i in range(6, len(pkt), 1):

278 msg = msg + b" " + pkt[i]

279 # Ensure msg length does not exceed Mongo's Index Key Limit

280 if len(msg) > 512:

281 msg = msg[:512] + b'...'

282 breakDad, your code could be incredibly, uh, organic. And not always the most deliberate. (sorry) It is exactly what you would expect from a solo C programmer circa 1990, which is basically what dad was. He would write a passable algorithm the first time, and then tweaked it with if statements over time, resulting in code that was less and less maintainable. Even though we were working in Python (which I think he really liked), his code structure was the good old C standby of “throw a bunch of functions into a file”. The mess of code above started out more copacetically.

233# Adding vlan id - PFG - April 2014

234# No way of knowing how long the packet is so add vlan id after timestamp.

235# If field after timestamp contains dots or colons, then it is a src (mac or ip).

236# Otherwise, it must be a vlan id.

237

238if pkt and not doc:

239 # If no vlan id present

240 if '.' in pkt[1] or ':' in pkt[1]:

241 msg = pkt[5]

242 for i in range(6, len(pkt), 1):

243 msg = msg + " " + pkt[i]... Still not beautiful, and you have to know what pkt and doc are, because they’re definitely not self-documenting, but you know, better.

And the stuff really worked. Dad understood better than most the value of simplicity in software architecture. Even though our system was spread across several processes, and each process might interact directly with the database, (a pattern that elicits shrieks of rage from most software designers I know,) every interaction was well documented and the documentation strictly updated. The flow of data was one-directional, and the state space was kept under tight control. We were careful not to introduce too many dependencies. The only frameworks we used were Debian Packaging, Pyramid, and BackboneJS. Everything else was a library. Though much of it was handwritten, the documentation was at least as good as any enterprise dev team I’ve encountered since. (Though not as good as most open source projects I’ve seen)

As we scaled the Sentry onto higher volume networks, Python started to groan a bit under the load. I ported a bunch of his ingest code to Cython over a few months, and Lo, his “let’s code this like it’s C” approach fit really intuitively with Cython’s “let’s turn this into C” approach.

You can’t buy the kind of startup experience I got working with Dad. Every mistake I made, every design decision, I was the one who had to take responsibility with the repercussions, just because we were a two-man shop, and he trusted me. I haven’t found that kind of learning environment anywhere else.

Technical things I learned from or with Dad:

- Early on we recognized the value a monorepo could bring, years before anyone used that word

- I hammered together a CI/CD pipeline from batch scripts. We judged Jenkins to be more infrastructure than we needed

- Instead of local environments, we developed remotely on instances of production environments, sidestepping an entire class of deployment issues

- We maintained multiple release channels and used feature flags to let us quickly respond to customers who wanted more now, without endangering customers who were happy with stability

- We managed an entire fleet of machines with only a few hours a month to coordinate software upgrades

More important yet was the concept Dad gave me that wearing lots of hats is fun. If you're from the future, wondering if I'd be a good fit at your company, just know that I will probably not be happy doing only one kind of work. With Dad, I:

- Slung Code in Python, Cython, JS and Bash

- Administered a Xen VM farm

- Designed a product UI

- Obtained my GPEN certification and performed pen testing against clients (because we were a security company)

- Used my own product to monitor client networks for security incidents

- Solicited customer feedback to improve my product

- Did sales engineering and support

- Designed implemented and shipped a marketing site (yes it's bad, but it's mine)

- Designed and chose chips for a custom form factor Ethernet tap, and worked with the hardware design firm to design and then test their prototypes

Even more important yet were the non-work things Dad taught me. But that's a little out of scope today.

I guess that’s all

I can feel the coherence of this post falling apart, so it must be time to wrap up.

When I was little, I wanted to be just like my dad. I’m still trying to be. It breaks my heart that my sons will not have the chance to know him. I wish I could bring him back, but the best I can do is post some of his old code online.

I miss you, Dad.